ICTJ’s partner Afghanistan Human Rights and Democracy Organization (AHRDO) recently opened a new virtual museum and database dedicated to Afghan victims of conflict and human rights abuses. “The Afghanistan Memory House” not only preserves the memory of these victims but helps pave the path for truth and justice. To launch the virtual museum, ICTJ and AHRDO cohosted a panel discussion on memorialization in ICTJ’s office in New York this past December. BBC journalist Lyse Doucet moderated the panel, which included AHRDO director Hadi Marifat, ICTJ senior expert Ruben Carranza, Afghan war victim Yaser Qubadian, and Medico International’s Thomas Seibert.

“In more than 40 years of war, there have been many painful years, but the last few years have been intensely painful for so many,” said Lyse Doucet. “And it’s really good now to see people emerging, Afghans and non-Afghans, and being more proactive, finding energy and resolve, again, to deal with these issues.”

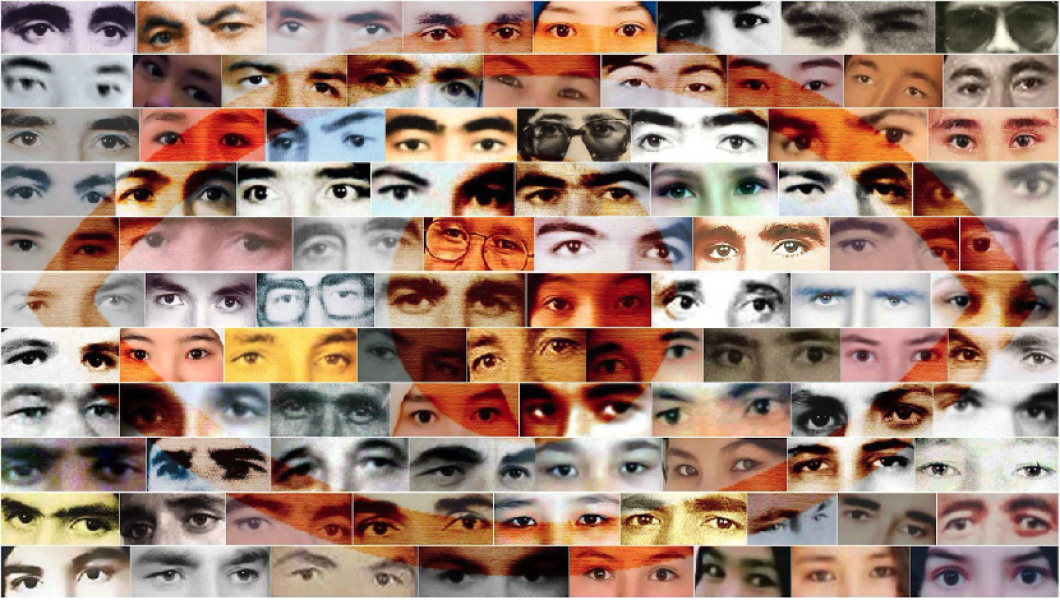

A virtual museum and victim-focused documentation center, the Afghanistan Memory House acts as secure repository of information that preserves the individual stories of victims and survivors. It includes government documents, photos, and other data sources, as well as images of victims’ personal items that loved ones collected and donated to AHRDO. One of the main goals is to show the human face and dimension of these victims, and that they are more than mere numbers or data points. For Afghans around the world, it offers a safe place to honor those who lost their lives, reflect, and find some form of healing.

“This is the continuation of the work we did in Afghanistan,” explained AHRDO’s Hadi Marifat. “The objective has not significantly changed from the objective of [AHRDO’s] center for memory and dialogue in Kabul. Although this platform is now digital [and] we were so far and in exile . . . [we] still tried to preserve and honor the memories of war victims and promote remembrance among the Afghan communities both inside Afghanistan, but also [those] in exile and Diaspora communities.”

The Afghanistan Memory House also aims to contribute to any present or future transitional justice process. Its collection of documentation and artifacts can serve as evidence of crimes committed and testimony of lived experiences in any number of formal or informal justice-related initiatives, including criminal proceedings, truth seeking, reparations, and other public awareness and memorialization campaigns. By digitizing the information sources, AHRDO has also better preserved them for use in any such effort in the near future or in generations to come.

The panelists discussed the decades of the violence in Afghanistan and the innumerable human rights violation perpetrated against the Afghan people. Acknowledging the massive challenges in pursuing criminal accountability in the present circumstances with the Taliban in power, the panelists underscored the value of other forms of justice that promote collective healing and provide redress for victims.

Panelist Yaser Qubadian shared his story as a survivor of a suicide attack and the brother of one of the victims who died in the same attack (his then 14-year-old sister). His testimony served as a potent reminder of the severity of these violations and their rights to redress and justice.

“[My sister and I were] raised as orphans. My father [was killed by] the Taliban on February 26th in 2006 when I was 3 years old and [my sister] was only a year old. [My sister and I] were friends, we were like father and daughter, and even classmates sometimes,” he recounted. “[Going] back to this memory sometimes is getting very hard for me but what I believe is that these are the memories that guided me through my journey and will guide me through the rest of my journey, through my life, or even to work [toward] something to avoid these things.”

“It’s important to remember that justice isn’t just punishment or prosecution and presenting evidence against perpetrators, [since] sometimes that form of justice may not be available,” stressed ICTJ’s Ruben Carranza. “We work on truth seeking. We work with and for victims and survivors to obtain reparations for the pain, the loss, the suffering, and the sadness they suffer. It's important to acknowledge that. And reparations aren’t punishment or prosecution, but they [still] are a form of justice.”

Documentation and memorialization initiatives such as the Afghanistan Memory House not only help affirm victims’ dignity and preserve their memory, they may be the best available course of action for justice at this time in Afghanistan’s history. “We have a world crisis and it’s at every layer: We have a social crisis . . . a political crisis, an ecological crisis . . . It’s a crisis of wars and violence. And so, [for] the task of civil society, if we are not able, at the moment, to really change the situation . . . then memorialization [must be] one of the main tasks,” asserted Medico International’s Thomas Seiber. “We are keeping the memory in order to hand it over, hopefully, to generations of times only to come, so that they can connect to the experiences we have.”

_______________

PHOTO: Courtesy of AHRDO.