By Sean Yoes

On a chilly Saturday night in February, several members of the Brown Grove Preservation Group, gathered at Around the Table, a Black-owned soul food restaurant in nearby Ashland, Virginia. For most of the night, roars of laughter emanated from the large table, as the members, all of whom are related by blood or marriage, dined on fried catfish, pork chops, collard greens, and other southern dishes and playfully teased one another. But the jubilant mood quickly turned somber when the subject of the planned construction of a 1.1 million-square-foot Wegmans distribution center in the heart of their town came up.

Founded in 1870 by formerly enslaved Americans, Brown Grove remains a small, tight-knit majority Black community. Unfortunately, the impending commercial development threatens to disrupt this peaceful place and its rich history.

Residents, activists, and others have been fearful for the future of their community ever since former Virginia Governor Ralph Northam announced in an official statement released by Hanover County in 2019 that Wegmans Food Market, Inc. intended to invest $175 million over three years to establish a full-service, regional distribution operation in the area.

Despite widespread community resistance, controversies over crucial permit acquisitions, the possible desecration of sacred burial sites, and numerous environmental concerns (the future facility will endanger several acres of federally protected wetlands), construction has commenced. Wegmans plans to open the distribution center sometime in 2023. All of this comes with the apparent blessing of Hanover County and the Commonwealth of Virginia. “The county doesn’t want to acknowledge Brown Grove,” said preservation group member and the community’s unofficial historian Diane Smith Drake, over a plate of fried catfish. “Never has,” added Renada Harris, the group’s leader.

A History of State-Sanctioned Industrial Encroachment

For nearly 70 years, Brown Grove, recognized by few outside the community, seems to have always been an option on the table when the state of Virginia and Hanover County sought to expand industry. For example, in the late 1950s, construction of I-95 began, which ultimately cut Brown Grove in half. (The highway was later enlarged in Brown Grove between 2015 and 2017.) In 1969, Hanover County Municipal Airport was built in the town. Years later, a proposed expansion of this airport forced some residents to relocate, even though according to community leaders that expansion never actually took place. There two concrete plants were also built in or directly adjacent to Brown Grove. And in 1987, work began on a commercial landfill—or “stump dump,” as it is often called—and recycling center in the historic community.

“When you live in a community where you are near [I-]95, you have the fumes; and, more importantly, we are by a truck stop, so you have all the emissions from the tractor trailers, and you have the fumes from the airplanes flying overhead every day,” said Harris. “The pollution is absorbed in those trees…. When you don’t have those trees to absorb the pollution, then that affects our air quality, and the roots from those trees protect the well water that some of the community has,” she added.

“Over the years, we have seen things slowly fall off and decline, the community getting smaller and smaller, mainly because of industry and the things that have been going on and the potential things coming up,” explained Kenneth Spurlock, chairman of the deacon board at Brown Grove Baptist Church. Deacon Spurlock notes the generational effects of this ceaseless encroachment. “It’s hard in today’s world for children who grew up here to come back when you have so much industry building up. It’s hard to say, ‘Well, I’m going to build a home in Brown Grove right beside a concrete plant.’ Or ‘I’m gonna buy my momma’s home place and live up here by the stump dump.’ And now you got Wegmans coming across the street.”

Born and raised in King William County, Virginia, Deacon Spurlock moved to Brown Grove in 1988, when he married his wife, Melinda, whose family has lived in the historic Black community for several generations. Spurlock’s heart has been in Brown Grove ever since. “We’re always dumped on. We have loving people, caring people, taxpaying people, and we’re involved in the communities. The church does tons of outreach,” he explained. “But when it comes to this community, I guess they consider it more of a valuable piece of real estate for industry.”

A Pattern of Disruption to Black Communities

Unfortunately, the Wegmans facility is not the first industrial incursion of its kind. This pattern of disrupting Black communities via federal, state, or locally mandated projects has been repeated for decades, in Virginia and around the country.

For example, Union Hill, Virginia, another majority Black community founded by formerly enslaved people after the Civil War, was similarly threatened by the construction of a 600-mile Atlantic Coast pipeline. Like Brown Grove, residents feared the uprooting of historic gravesites, as well as increased air and water pollution connected to a compressor station necessary for the pipeline’s completion. Last year, they came together and were able to block the pipeline’s construction, demonstrating the power of community engagement and collective action.

At the national level, federally funded interstate projects have disrupted numerous Black and other disenfranchised communities. After President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, Brown Grove was one of the first Black communities adversely affected by the construction of Interstate 95 (I-95), which began in the 1950s. The proximity to I-95 is one of the main reasons cited by Wegmans for choosing Brown Grove as the location for its distribution facility. Other, similar projects have divided Black communities in Detroit, Los Angeles, Miami, Nashville, and New Orleans, among many others.

“What is happening in Brown Grove is not an anomaly. This is a community that has been repeatedly denied its fundamental rights. And unfortunately, this denial of rights is part of the larger pattern of systemic racism in the U.S. that needs to be acknowledged, redressed, and prevented. The Wegmans incursion must be seen as both an environmental justice issue and a transitional justice one,” explained Virginie Ladisch, a senior expert at the International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ), an organization that works in societies around the world grappling with legacies of massive human rights violations.

Seeking Redress for the Latest Injustice in Brown Grove

Today, the fear is that the arrival of the Wegmans facility will make life in this once idyllic community intolerable. Known as the Air Park Associates site, the large parcel of undeveloped land that will house the massive center is located directly across the street from the venerable Brown Grove Baptist Church on Ashcake Road. The future employee entrance, which will accommodate approximately 700 Wegmans workers, and will stand just a few yards from the entrance of the church. The facility will encroach directly on several properties owned by Brown Grove residents, and there is great concern about potentially drastically increased traffic and noise, as well as decreased air and water quality.

The massive distribution facility will also literally cast a shadow on the heart of the community: Brown Grove Baptist Church. Residents are adamant that the facility’s presence will require them to build another centrally located hub for various activities serving Brown Grove as well as nearby communities. “We would like a community center. When you take away the ability of our kids to freely play…because of the accidents the increased traffic will cause, we want a place where they can come and be safe, off the road where they can exercise without them having to breathe in any pollution,” said Harris. “We don’t have to have activities at the church; we could have them at a community center, not only for the church but all of Ashland and Hanover as well.”

Wegmans certainly had other options besides Brown Grove. In fact, it considered several sites, including multiple locations in North Carolina, but Virginia gave Wegmans at least $4 million and other incentives to encourage the company to come to the state. Even within Virginia, Wegmans had at least four other options. It allegedly chose Brown Grove over an identically sized site in northern Hanover County. That site was temporarily under contract with home improvement retailer Lowe’s at one point, but the deal fell through and the lot remains unoccupied.

Hanover County’s official release announcing the development reads: “The Virginia Economic Development Partnership worked with Hanover County and the Greater Richmond Partnership to help Wegmans find a property that could meet its needs in Virginia.” However, the irony for many in Brown Grove is that state of Virginia and Hanover County clearly gave little or no consideration to the needs of Brown Grove residents. As Harris put it, “Wegmans will benefit from generational wealth on behalf of the industrial injustice that Hanover has put on Brown Grove.”

The community center that residents are asking for is one way to mitigate the harm that the distribution center will cause. Residents are also calling for action to preserve Brown Grove’s rich and storied history, one that is very much emblematic of the United States’ long record of systemic racism.

Brown Grove’s Historical Memory Must Be Preserved

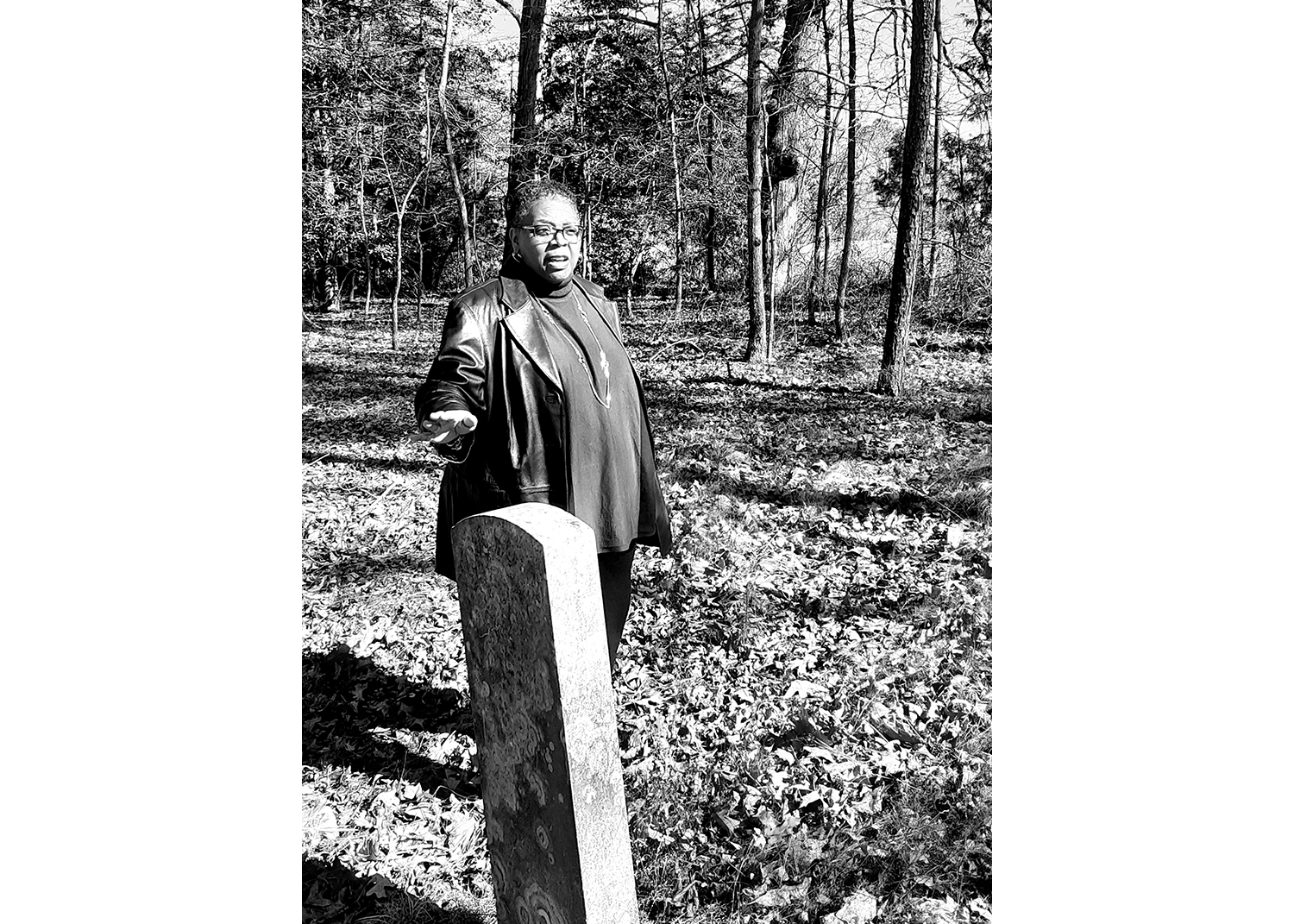

The current residents of Brown Grove carry with them the heavy truths of their ancestors. After a 10 a.m. church service at Brown Grove Baptist Church one recent Sunday, Diane Smith Drake, the unofficial historian, headed to a small, nondescript graveyard near a wooded area on the church’s property. Several of Smith Drake’s ancestors are buried there, all of whom helped build the church. “Six people started a ‘brush harbor’ in 1870, which was directly after the Reconstruction era…They wanted a place to worship,” explained Smith Drake. “A brush harbor is nothing but branches put together as a shelter, and they worship in this shelter. That’s all it was. They still couldn’t worship out in the open. Some people call it a ‘hush harbor,’” she added.

That same year, in 1870, Caroline Morris, a freed Black woman who was born enslaved in Hanover County in 1846, is credited with founding the community. Morris is now referred to with deference as “the mother of Brown Grove,” and many of today’s residents claim direct lineage to her.

According to Smith Drake, several early wooden church structures were destroyed in fires throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries. “Many said, back in that day, they couldn’t prove that it was the KKK, but that was the normal thing for those churches back in that era,” she explained. “Our modern-day church was built in 1945, and the community, the men, would take part and come after they worked all week and help build this church,” Smith Drake added.

Later that same Sunday, after a much-anticipated meal following church service at her mother and father’s house, Renada Harris walked through her family’s burial site behind their home. Known as the Lewis and Morris family graveyard, some of the graves are mere feet from the property line of the planned Wegmans distribution facility. It is widely believed that Caroline Morris is buried there in an unmarked grave.

One-hundred and fifty years later, this community’s rich foundations and unique history are imperiled by what many say is the state and county’s irresponsible efforts to industrialize the area. Corporations and governments—local, state, and national—must do a better job of honoring the legacies of the past, listening to the communities they aim to serve, and meeting their demands.

“Unfortunately, we always see a disconnect between what local elected officials want compared to what their communities want,” said Delegate Elizabeth Guzman, who represents Virginia’s 31st House of Delegates district, which includes Brown Grove. “I think that our commonwealth needs to start supporting our historically Black communities, and we must prioritize their inclusion….We need more people to share their stories like the Brown Grove community has,” she continued. “The Brown Grove community has time and again been subjected to environmental racism and encroachment. Being inclusive means respecting both sides, and what does that mean for the Black community in Brown Grove?… It’s not right.”

One critical way to deal with historical injustices and preserve memory in a community such as Brown Grove is to create inclusive spaces for community members to convene and discuss their grievances, as well as their demands for redress.

Along these lines, ICTJ, in partnership with the African American Redress Network, organized a community empowerment retreat in Brown Grove in November 2021. The two-day workshop brought together residents, activists, and civic leaders to discuss what they wanted for the community, including reparative measures, and to develop clear goals and an actionable plan to obtain them. Discussions such as these, in which all members of the community can participate and have a voice, represent the type of public engagement and effort to galvanize broad public buy-in that should be part and parcel to all major development plans that affect tight-knit but marginalized communities like Brown Grove.

A Community Voices Its Demands for Justice

First and foremost, the Brown Grove Preservation Group has long demanded that Wegmans relocate the distribution center elsewhere. “We want our community to be recognized and for Hanover County to treat it with the respect that an historic preservation site deserves. We want Hanover County to invest in our community with parks, walkways, and the community center. This isn’t unreasonable, since it is reflective of the other side of town that is predominantly white,” Harris explained.

Given that construction has already commenced, a clear indication that Wegmans is unlikely to back down, the preservation group is ready with other demands. As mentioned, the group is asking the company to support the construction of a community center that would serve the entire area, since the facility and the comings and goings of its employees will disrupt many of the activities that currently take place at the church. In addition, it is demanding other specific remedies for the succession of historic environmental injustices.

According to Harris, “We want clean air and clean water to mitigate the amount of toxins flowing into our community as a result of all the industry. These are reasonable asks from the county, from the DEQ [Department of Environmental Quality], and from the Army Corps of Engineers. We want a moratorium on further encroachment to be implemented for Hanover Country.”