By Eduardo González Cueva, Director, ICTJ Truth and Memory Program

On April 24, seven and a half years after the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement, Parliament voted to establish the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) and a Commission of Investigation on Disappeared Persons (CIDP).

Given the long wait, some expected victims’ organizations and human rights groups to be ecstatic; but in fact, the opposite is true. They have strongly rejected the bill because—they claim—it will allow the commission to recommend amnesties for perpetrators of gross human rights violations.

Some government leaders have defended the bill and urged the public to move on to other elements of the national agenda, like negotiating the new constitution. They can’t deny that the commission may recommend amnesties, but they say such a step would only happen with the victims’ consent.

The debate is extremely important for Nepal because it affects the quality of the peace process and the democratic system the country has vowed to build.

As a Peruvian human rights activist and a former staff member of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission created in my country, the questions raised in Nepal touch a deep nerve. Peru suffered a 20-year armed conflict that left more than 69,000 people dead, including approximately 15,000 victims who were forcibly disappeared.

Why is the truth so important after so devastating of a conflict? Why do victims care so much about justice? Wouldn’t it be better to let bygones be bygones? These questions, which I’ve heard from Nepalese colleagues and friends, are quite similar to ones I heard in Peru and other countries when the time for the truth came. Allow me to offer three reasons.

First: prevention. Truth is important to identify the reasons why a country was torn apart in an explosion of violence. Society needs to examine the motivations of the fighters, the social conditions, and the strategies that led citizens of the same country to fight each other. If this inquiry is not conducted, what guarantees are there that the violence won’t be repeated?

Second: healing. Victims often experience deep trauma, some are left with torn bodies, others are left impoverished. Worst of all, most see themselves humiliated and stigmatized. Victims need a chance to be heard with care and respect by the top authorities and their fellow citizens, to be able to believe again that their country is indeed a home for all.

Third: rule of law. Peace cannot be built on the basis of violence; democracy cannot be built over authoritarian imposition; law cannot be built on the denial of rights. The victims have a universally recognized right to know what happened and the reasons and the responsibilities for the facts.

The problem with the legislation recently approved in Nepal is that it doesn’t address any of these important needs. The TRC and the CIDP will examine isolated incidents in which—the bill assumes—it will be possible to identify and bring together individual victims and perpetrators to reach an out-of-court resolution.

Such an approach does not serve prevention because the commission will spend its energies pursuing a case-by-case approach, without being able to understand and present the larger trends of the conflict. A simple review of the final reports of truth commissions reveals that they do not exhaust their work in individual cases, but make large societal findings, in order to make recommendations aimed at the prevention of crimes.

The model set by the bill does nothing to heal victims. It is doubtful that the commission would be able to identify individual perpetrators in each case, and if they were able to, it is uncertain that perpetrators would want to clear their conscience with a full confession. Even worse, the bill ignores the fact that impoverished victims who likely are in difficult psychological and financial situations may be scared to confront powerful perpetrators and may accept a fake act of “reconciliation” out of pure fear and desperation.

Victims who come before the Commission on Disappearances will face the same mechanisms. But the bill is scant in details, leaving open questions on whether the commission will do what the relatives of the disappeared need foremost, which is the actual, specialized search for the fate of the disappeared and in the case of their death the recovery of their bodies, to honor them, according to their beliefs and traditions.

Finally, if the commissions are able to recommend something illegal, like amnesties for disappearances, torture, or arbitrary executions, they will ignore human rights obligations and the rule of law. These are not merely “international” obligations, but clear Nepalese standards affirmed by the bill of rights in the Constitution, the treaties signed by Nepal, and the principles affirmed by the Supreme Court.

The sad fact is that, as it stands, the bill responds to only one misplaced expectation: that no crime committed during the conflict will be tried in a court of law. But instead of accepting the responsibility of creating a system of justice able to take realistic and fair decisions on this issue, Parliament decided to place the issue squarely on the shoulders of those who have suffered the most: the victims.

This is simply unfair. Victims groups are right to be deeply worried, and the public should be too. But the leaders of the main political parties should also realize that insisting on this bill is a risky path. A truth commission or a commission on disappearances should be created for the sake of the victims, so that they can heal and be helped by a society that shows them solidarity and respect. If victims reject the commissions, they may simply not participate, or—worse—participate, be disappointed, and denounce bitterly the entire effort. Such a result would be deeply embarrassing for Nepal and its leadership.

Going back to the case of Peru, our truth commission was far from perfect, and we still have a long way to go to affirm our democracy and the rule of law. However, our truth commission, with all its limitations, gave victims a direct platform to tell the nation how they suffered and be recognized in their dignity and rights. Having suffered too the horrors of an internal conflict, I can only hope that the victims in Nepal will have the same opportunity to assert their powerful voices.

Originally published in the Kathmandu Post

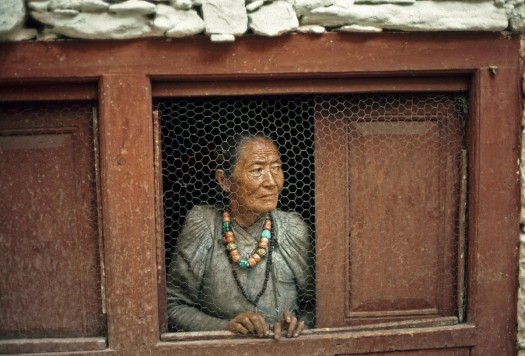

PHOTO: UN Photo/John Isaac via Flickr