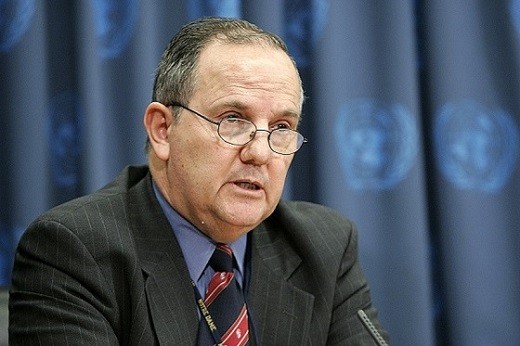

On 26 June each year, the world marks the International Day in Support of the Victims of Torture. The day was instituted in 1997 by the General Assembly of the United Nations, in an effort to build up the unanimity of condemnation required to abolish torture effectively in our time. In the effort to draw attention to the struggle against torture that this international commemoration signifies, we spoke to Juan Méndez, the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture and President Emeritus of ICTJ.

A native of Argentina, Juan Méndez has dedicated his legal career to the defense of human rights and has a long and distinguished record of advocacy throughout the Americas. As a result of his involvement in representing political prisoners, the Argentinean military dictatorship arrested him and subjected him to torture and administrative detention for more than a year. During this time, Amnesty International adopted him as a “Prisoner of Conscience.” After his expulsion from his country in 1977, Mr. Méndez moved to the United States.

“The significance of this day is that it attempts to recruit victims and survivors of torture to that struggle, in the belief that more and more members of society will realize the immorality of torture when they can put a human face to the pain and suffering that it inflicts,” says Méndez

We are marking the 30th anniversary of the UN Convention against Torture. How do you see the new initiative for its universal ratification and implementation?

The Convention against Torture (CAT) is an excellent normative framework for the struggle to abolish torture in practice (because in law it is firmly prohibited). The CAT's provisions are all customary international law (and the prohibition of torture and ill-treatment is, additionally, jus cogens) so they apply also to states that have not ratified it. In the less than three decades since CAT was approved, it has achieved a significant number of ratifications. Nevertheless, it is important to make a push for universal ratification, so as to eliminate any argument about the universal nature of its very specific provisions, such as the obligation to investigate, prosecute and punish each instance of torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, the specific non-refoulement provision, the exclusionary rule, the obligation to offer reparations and rehabilitation to victims, and - significantly - the obligation to prevent torture. That is why my mandate enthusiastically supports the initiative of several states to promote universal ratification of CAT, in the understanding that thereby we also promote effective implementation, in good faith and with due diligence, of all its provisions.

Which states or regions of the world are particularly problematic at present for perpetrating torture? What if anything is being done about it?

Unfortunately, no part of the world is safe when it comes to torture, although it is true that torture and ill treatment come in so many ways that it is hard to compare. Powerful democracies do not torture their citizens but their agents perpetrate torture extraterritorially and, what is worse, those crimes go uninvestigated and unpunished. In many emerging democracies there is no longer torture of political enemies, but the state of prisons for common crime offenders is appalling. Even model democracies have recourse for solitary confinement, which can be - given appropriate circumstances - mental torture or ill treatment. In criminalizing protest, many countries use excessive force that can amount to torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment. And of course, where there is armed conflict there is also a proliferation of instances of outrages against the personal dignity of combatants and of civilian population.

The push for global ratification of Convention against Torture is focused on states, but it is not always the state actors who perpetrate it. How can we deal with torture committed by non-state actors?

The laws of war give us the legal tools to combat torture by non-state actors, at least when it comes to armed conflict. We have the International Criminal Court and we must insist on the triggers to its jurisdiction whenever there is reason to believe that non-state actors commit crimes under the Rome Statute. In some cases it will be necessary for the Security Council to refer the case; in others it may be possible for the Prosecutor to initiate cases proprio motu. For cases not covered by the ICC, we can promote the use of universal jurisdiction, since torture is an international crime that justifies the use of courts of all nations under that principle. Outside the realm of armed conflict, international law has made great strides in addressing domestic violence as torture, in circumstances in which the state knew or ought to have known that a person was at risk. In those circumstances, the state is responsible for its violation of the prohibition of torture, towards the victim as well as toward the international community.

In your opinion, how best can we restore dignity to the victims of torture?

We restore dignity to victims and survivors by offering reparations and rehabilitation that do no insult their worth as victims and as citizens. Reparations must be designed to symbolize the recognition that the victim is no longer treated as a second-class citizen. More importantly, we restore their dignity by allowing them to participate actively in all aspects of the state's obligations under CAT: in the design of reparations schemes, in the active prosecution of perpetrators, and in the demonstration that torture has occurred for purposes of the exclusionary rule.

How big of a role does the prosecution of perpetrators play in the restoration of dignity? Does this change when amnesties are granted to perpetrators?

The most important reparatory right that victims have is to see justice done. If we don't prosecute torturers we deprive their victims of their right to a remedy. An amnesty that has that effect is a new violation of a state's obligations under international law, and it definitely demeans and humiliates the victim of torture.

How effective is the UN Voluntary Fund for Victims of Torture? What can be done to ensure its financial sustainability?

The UN Fund provides essential support to frontline organizations that carry out indispensable activities in monitoring and denouncing torture, in protecting and restoring victims to productive lives, and in preventing torture by various means. It undoubtedly could do a lot more if states took seriously their responsibility to ensure its financial stability and long-term projection.

The Anti-Torture Initiative at American University’s Washington College of Law recently launched a website and social media campaign on the theme of “Working Together for a #TortureFreeWorld.” Can you tell us about this, and how you believe individuals and the media can play a role in creating a visible impact on efforts to support victims of torture?

The ATI is a project of the Center for Human Rights and Humanitarian Law at WCL, designed to support the work of the Special Rapporteur on Torture, especially in the areas of follow up and dissemination (where the support provided by the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights is very low or non-existent). The webinar of this week is an attempt to generate a discussions among our partners and all interested parties about how best to use of the occasion of the International Day in Support of the Victims of Torture to reinforce our common commitment to obtaining a torture-free world, a goal that seems very idealistic but that many of us think is or should be within reach.

*PHOTO: Juan Méndez, the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture and President Emeritus of ICTJ. (Mark Garten/UN)*