ICTJ released a briefing paper today examining current opportunities for prosecuting serious crimes within Kenya’s national judicial system, including crimes committed during the postelection violence of late 2007 and early 2008 (PEV), which claimed 1,113 lives and displaced an estimated 660,000 people.

Titled “Prosecuting International and Other Serious Crimes in Kenya,” the paper looks at legal and institutional reforms that may be needed at the national level to effectively investigate and prosecute the worst crimes of the PEV period, including murder, serious assault, and rape.

While Kenya has made significant efforts to address its legacy of violence during the postcrisis period, domestic criminal justice processes have been limited.

Kenya’s Commission of Inquiry into Post-Election Violence (or Waki Commission) published its report in October 2008, finding evidence of massive failures by state security agencies during the PEV, especially the police. It recommended that a special tribunal be established to prosecute PEV-related cases.

In December 2008, Kenya also passed the International Crimes Act to domesticate the Rome Statute of the International Criminal. However, the law only applies to crimes committed after January 1, 2009, putting it beyond the scope of PEV cases.

In 2012, the International Criminal Court (ICC) confirmed charges against current Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta (then Deputy Prime Minister), current Deputy President William Ruto, and former Kass FM radio presenter Joshua Sang, for crimes against humanity, forcible transfer, and other crimes allegedly committed during the PEV.

Kenyatta is now the second sitting African president to face ICC charges. His trial is scheduled to begin on July 9, 2013. Ruto and Sang’s is scheduled for May 28, 2013.

The Kenyan government, however, has repeatedly stated that it wants to prosecute PEV cases locally and bring the ICC cases home. Yet, the ICC rejected an admissibility challenge by the government, noting there remains a “situation of inactivity” in Kenya. Doubts remain as to Kenya’s capacity and willingness to try high-level offenders.

As the paper explains, to try these types of cases, the national courts will need to conduct impartial proceedings, and all sectors and individuals who are involved will need to respect the separation of powers and the rule of law.

The report recommends that the Kenyan Parliament adopt legislation to establish a special prosecutor with all necessary powers to effectively deal with PEV cases and the High Court should create a special division to prosecute serious crimes.

"While the formation of a special division of the High Court is welcome in principle, the government must not stop there,” says Njonjo Mue, head of ICTJ’s Kenya Program. “Without genuinely reforming other justice-sector processes, such as investigations, prosecutions, and witness protection, the special division will not succeed.”

The urgent need to address Kenya’s impunity gap was highlighted by the ongoing violence in the run-up to the March 2013 elections, including in Tana River and Baragoi. In the Tana River clashes—which left more than 100 people dead and thousands displaced—two members of Parliament, a minister, and other leaders were implicated.

As the briefing paper concludes, the government must ensure that serious crimes are swiftly and independently investigated and prosecuted, regardless of whether political actors or other powerful individuals may be implicated.

It is therefore vital to strengthen the capacity and independence of Kenya’s existing legal-sector bodies, to promote accountability principles in the long term.

Listen to ICTJ experts discuss Kenya's March 2013 elections in this recent episode of the ICTJ Forum

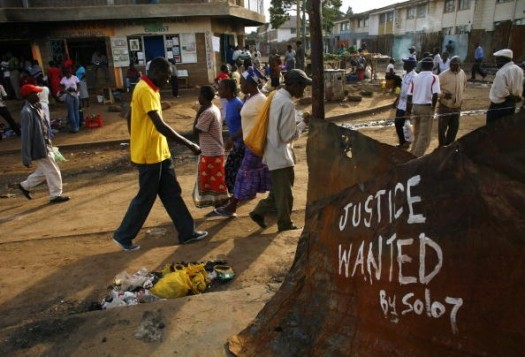

PHOTO: Kenyans walk along the main street of the Kibera slums painted with a political statement February 10, 2008 in Nairobi, Kenya (Paula Bronstein/Getty Images)