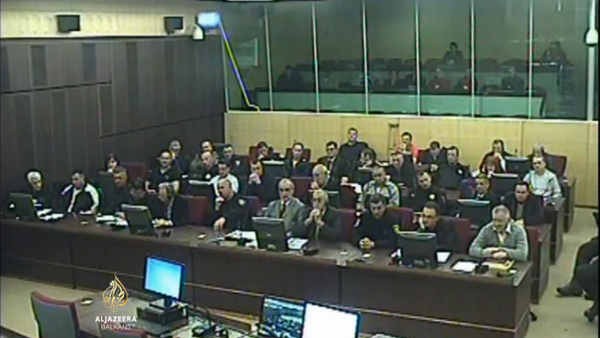

In the morning of April 17th this year, fourteen men filed into the high security courtroom of the Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina in silence and took their places in the first two rows of chairs assigned to the accused. Several were in their mid-forties, most in their fifties and sixties; a couple of them wore suits while the rest were dressed in tracksuits and sport jackets, as if they were brought in from one of the many Sarajevo cafes lining the streets outside the building. A few of the older men seemed lost in thought, intently staring at their hands, seemingly trying to find the answer to their predicament in the maze of their intertwined fingers. Some of the younger ones looked around the room, nodded to each other, smiled awkwardly, tried to exchange a few words with their lawyers or the stone-faced guards sitting next to them.

Across the aisle from this strange group, on the other side of the high security courtroom, a lone prosecutor shuffled through his papers, occasionally turning to his assistant with a question or a nervous remark.

All present jumped to their feet as a side door opened and three judges, two men and a woman, donned in heavy, dark robes, walked in and took the bench. The presiding judge, his face somber and unsmiling, likely dreading the horror of the story that was about to unfold in his courtroom, wasted no time on niceties and promptly opened the trial of Dušan Milunić et al, charged with crimes against humanity, murder, rape, plunder, unlawful imprisonment, and torture committed in 1992 in the village of Zecovi, near Prijedor, in north-western Bosnia. He invited Izet Odobašić, a prosecutor of the War Crimes Division of the State Prosecutor’s Office to present the charges. The gray-haired prosecutor stood up, pulled a document from the pile of papers on his desk, cleared his throat, and started speaking.

***

Although the sun was still not at its peak on that day, July 25th, 1992, sweltering heat had already enveloped the dusty parking lot of the local store in Rasavci, a village nestled on the left bank of the Sana river whose emerald waters curved through lush greenery as it continued towards Prijedor. The summer was hellishly hot that year, hotter than any Prijedor folk could remember.

Dušan Milunić and Radomir Stojnić lined up the men of the local reserve army unit, policemen, and a few armed volunteers. The youngest was 17, the oldest 67. Milunić, the commander of the Rasavci Company of the 43rd Brigade of the Bosnian Serb Army and Stojnić, the local police chief, issued the order: the men will follow them to the neighboring village of Zecovi, search for weapons, and complete the “cleansing” of the area, which had begun two days earlier when all the able-bodied Muslim men they could find were taken to the “Keraterm” concentration camp. The men from the company were all from the village and knew their neighbors from Zecovi. They had played football and fished together as boys, gone to the same schools, same cafes, drank together, worked together, lived together. But not anymore.

The company made its way through the winding road leading from the riverbank and up a small hill dotted with clusters of houses. Zecovi was known in the early 1900s for its reserves of highly prized clay used for ceramics that would draw merchants from as far away as Italy. But today its history did not matter. After today it would be erased and a new history would begin.

Milunić ordered house after house searched, ransacked, then burned to the ground. First several were empty. In others there were people, mainly women. “Where are the weapons?” — the soldiers shouted while trashing the place — “Where are the men?” Whoever they found was rounded up and shot. Seven at the main intersection, twelve in the courtyard of the village school, five in front of a pub where they had all drank together just months before. The heat of the July day and their gruesome work soaked the soldiers’ uniforms with sweat. The hills were silent except for the crickets, a witness would later recall.

Further up they packed some 40 people into a house and boarded up the doorways and windows, then one of the men, Bosko Grujicic, known for the hunting dogs he bred, set it ablaze. The company stood with their guns at the ready, to make sure nobody escaped as the flames licked the roof amid the deathly screams from the inside. Once the screaming subsided, and the giant blaze started flickering down, they passed a bottle of plum brandy around to wash down the dust and pick themselves up. The sun was slowly descending but their job was not finished.

They had played football and fished together as boys, gone to the same schools, same cafes, drank together, worked together, lived together. But not anymore.

Some five hundred meters further up the road, Zijad Bačić hungrily swallowed a piece of bread with butter handed to him by his mother Šida. Šida brought her daughter Zikreta and three sons — Zikret, Zijad and Sabahudin — to her cousin’s house to huddle with 26 other women and children and wait for the soldiers to pass. The men were taken away two days earlier, and as lonely houses were scattered across the hilly terrain, they sought safety in togetherness. Zijad’s mother said something about eating slowly as she passed the rest of the bread from the tray to Zijad’s cousins Nermin and Nermina, gently stroking their blond hair. They cried a lot. They missed their father Fikret, stuck in Germany where he worked odd jobs to save up for a house he had started building last summer. As soon as he comes back, grandmother Šehrija would tell them, he would make this nightmare go away and no soldiers would dare come to their house. Zijad was still hungry and thought of asking Nermin for his piece (he was not eating it anyway, instead, sobbing into it), but his mother saw his intent and shook her finger at him: “Don’t you dare!” At that moment a volley of gunfire exploded under the window. “Get the fuck out of the motherfucking house, you filth!,” thundered a voice Zijad thought he could recognize. Children screamed. He hugged Zikreta, who was shaking violently, soundlessly. The door crashed in under the boot of a large man reeking of alcohol. “Get out, get out, what the fuck are you waiting for!”

The group started streaming through the door into the dusky courtyard. Zijad was frantically looking for his shoes, but could not see them through the forest of legs and long skirts as women led their children out of the house. Finally, he spotted them under a broom by the door. He put his right shoe on and hopped out onto the veranda trying to put on the other. Everyone was already outside, gathering at the other side of the yard, mothers clutching their children, huddling in strange silence, retreating towards the center under the soldiers’ curses, trembling together like some sort of a terrified super organism. Without a warning a bearded man with sunglasses started firing. Others joined. Zijad’s other shoe fell from his hand. Volley after volley, bullets sprayed the huddled bodies, mechanical explosions morphed into one long thunder-like sound echoing across the rolling hills. Smoke covered the yard, and Zijad could hardly make out the silhouettes of the soldiers moving through it as he dashed behind the house and hid in the tall weeds behind the garden. As the automatic weapons went silent, he could hear the individual shots of pistols.

The boy lay for hours on his back motionless, dazed, staring at the sky illuminated by the flickering flames devouring the house. He could feel the warmth of the fire on his face, night bugs crawling on his hands, but dared not move. As it started dying down and the darkness enveloped the surroundings, he slowly got up and started walking towards a house on the neighboring hill that had its lights on. It belonged to his friend from school, a Serb. He passed the barking dog chained to the gate and knocked on the front door. The neighbors took him in, hid him for the next eight days until they were able to smuggle him out to a distant relative who was still alive in the old part of Prijedor. Soon after, Zijad made it to central Bosnia in a convoy of deported Bosniaks [Bosnian Muslims] and Croats. He made it out alive, but his friend and his friend’s father who saved him did not. A couple of months later masked killers gunned them down in front of their house.

***

For more than three hours, prosecutor Odobašić continued to read out the gruesome details of the crimes alleged in the indictment against the fourteen men sitting across the aisle. Over those several July days in 1992, neighbors from Rasavci had killed more than 150 people in Zecovi, raped numerous women, and laid waste to the village they had grown up next to. Most of the bodies, including those of 33 women and children killed on the 25th of July, were never found. The prosecutor finished by stating his intention to call 93 witnesses and submit more than 400 pieces of evidence. The presiding judge turned to the accused: “You’ve heard the charges, how do you plead?” One after another, the fourteen men from Rasavci stood up and declared: “Not guilty.” The thick bulletproof glass separating the courtroom from the public gallery muffled the angry shouts of abuse from a handful of victims’ family members in attendance. The judge called the room to order until each of the accused entered his plea and adjourned the trial until the following week, when the first witness was to testify.

The trial chamber exited the courtroom, followed by the prosecutor and the procession of the accused and their lawyers. The public gallery emptied as victims’ families trickled out to face the throng of reporters waiting to hear if they were satisfied that the alleged killers were facing the bar, albeit 23 years after the crimes had been committed. The courtroom was empty but for a man in his fifties with short blond hair and piercing blue eyes sitting quietly in the last row of the public gallery. The expression on his face was mournful, yet it radiated content and something else, determination perhaps. In silence he got up and walked over to the glass, placed his palms on it and stood like that for a while, gazing over the courtroom. His eyes stopped at the witness stand where he was to appear next week as the first witness. He was to testify about the killing of his two children, Nermin and Nermina, his wife, his mother, and 14 other relatives. His name was Fikret Bačić.

Prijedor, a rupture

It was in the late spring of 1992 that the small industrial town of Prijedor, nestled in the foothills of the Kozara mountain, emerged from the blissful provincial obscurity of northwestern Bosnia to headline news bulletins across the globe, becoming synonymous with the full force of horrors unfolding in the Bosnian carnage.

By then, the violent breakup of Yugoslavia was well underway. In March of 1991, Slovenia had successfully seceded after a popular referendum, declaration of independence, and a brief altercation with the Yugoslav Army, already under the tight grip of then Serbian President Slobodan Milošević. Croatia was next.

There, the scenario was very different. Croatian Serbs rejected the newly established Croatian authorities as successors of the Ustasha regime, which in collaboration with their Nazi occupiers, had killed hundreds of thousands of Serbs during the Second World War. [Ustashas were a fascist regime headed by Ante Pavelić in the Nazi puppet state the Independent State of Croatia (NDH) in Yugoslavia during World War II.] With the help of the Yugoslav Army, still nominally acting in the interest of all the peoples of the former state, they set up their own police and territorial defense. Croatia could go, but Serb-controlled lands would not follow; instead, they declared them “Serb autonomous regions” intent on joining Serbia. The fuse was lit and it took an attack on a busload of Croatian policemen near the eastern town of Vukovar to set Croatia ablaze.

The complete annihilation of Vukovar, the shelling of the ancient city of Dubrovnik, massacres of civilians, refugees streaming out of frontline zones, and euphoric crowds in Serbia throwing flowers on Yugoslav Army tanks heading to Croatia were the hallmarks of the conflict. It raged until a ceasefire was agreed under the auspices of the United Nations in February 1992, effectively freezing the conflict. UN forces were deployed along the borders of the self-declared “Serb Republic of Krajina” and the fighting subsided. This peace largely held, with some flare-ups, over the next four years, until the summer of 1995, when the Croatian Army with the help of American instructors and intelligence, in an overwhelming blitz, destroyed the Serb statelet on its territory, expelling in the process more than 200,000 Serb civilians.

Meanwhile, in neighboring Bosnia and Herzegovina, the most ethnically mixed of all Yugoslav republics, the relations between its Bosniak, Serb and Croat populations were straining to the breaking point. Prijedor, with its ethnic mix where Bosniaks just slightly outnumbered the Serbs, was no exception. [According to the 1991 census, out of 112,543 citizens of the Prijedor municipality, 49,351 declared themselves as Muslims, 47,581 as Serbs, 6,316 as Croats, 6,459 as Yugoslavs and 2,836 as “Other”.] Bosniaks largely stayed out of the fight in Croatia, following the call of their leader and the president of Bosnia, Alija Izetbegović, not to respond to conscription calls. “Sleep peacefully,” Izetbegović famously declared, “there will be no war in Bosnia. This is not our fight.” Bosnian Serbs did not take him too seriously, however, and enlisted en masse.

The atmosphere in Prijedor darkened as the cracks in the cement of “brotherhood and unity” which bound its predominantly working class citizenry grew larger and deeper.

Volleys of gunfire became the soundtrack of Prijedor nights, as the Serbs started threatening secession if the planned referendum on Bosnia’s independence went ahead in February 1992. A unit of fearsome Serb paramilitaries called “Wolves” seized the main TV transmitter on Kozara, switching off all channels but those from Belgrade and Serb-held territories in Bosnia and Croatia.

In January, to preempt the referendum, Bosnian Serb MPs formed a parallel entity called “Serb Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina.” On February 29 and March 1, the referendum was held and Bosniaks and Croats overwhelmingly voted for independence. The European Union and the United States expressly recognized Bosnia and Herzegovina as an independent state. Serbian paramilitaries attacked the city of Bijeljina on the border with Serbia. Barricades were erected and clashes spread through the capital of Sarajevo.

In Prijedor, fear grew exponentially with the euphoria of nationalism. People withdrew to their homes. Many still hoped it would pass, that it would never reach them. The hope was feeble in the face of approaching cataclysm. What always seemed unimaginable now loomed as inevitable.

During the early morning hours of April 30, 1992, some 1,000 Bosnian Serb paramilitaries and reserve policemen, acting on the orders of Serb “Prijedor Crisis Staff,” seized control of Prijedor. Documents and transcripts of their meetings would later reveal that the seizure of physical control of the town was the culmination of preparations that had begun covertly in 1991, in conjunction with similar efforts throughout Bosnia and Herzegovina. In the following weeks, the new Serb authorities imposed strict restrictions on non-Serbs in Prijedor. All non-Serbs holding posts in the municipal government who did not publicly express full support for the new order and Serbian leaders were expelled from their positions. Businesses and public companies quickly followed, dismissing almost all non-Serb employees. Roadblocks were set up throughout the municipality to prevent non-Serbs from leaving the vicinity of their homes or villages. All non-Serbs were repeatedly exhorted and warned to turn in all their weapons. During this period, similar types of policies and actions were implemented in municipalities throughout the self-proclaimed “Serb Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina.”

Still, few were those who could anticipate the scale of the violence that was to be unleashed on May 23, 1992. Some three weeks after the takeover a coordinated attack was launched by forces that included the Yugoslav Army regulars, the Serbian “territorial defense,” paramilitary, and police units. More than two days of intensive artillery and tank shelling was followed by infantry assaults on Bosniak and Croat villages just outside the city. Hundreds were killed on the spot, in front of their homes, in this operation of “cleansing” of the municipality. The term would later be broadened into “ethnic cleansing” and would enter the vocabulary used to describe what was happening in Bosnia, and later Rwanda and elsewhere.

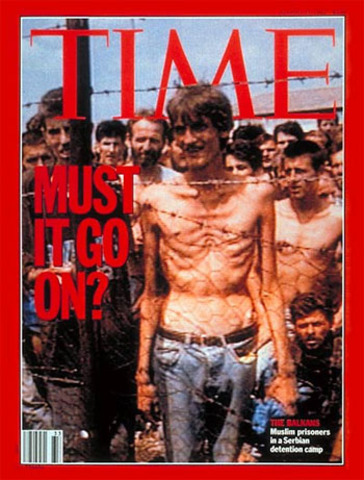

The majority of Bosniaks and Bosnian Croats who survived the initial attack fled their homes and were seized by Serb forces. The men were forced to march in columns to one or another of the prison camps established in the municipality, most of them to Omarska, “Keraterm,” or Trnopolje. Many were pulled from the columns and shot or beaten on the spot. More than 30,000 went through the camps over the next three months, enduring torture, daily beatings, hunger, overcrowding, and disease. Some 1,500 people died in those camps.

The final large-scale military attack took place on July 20, 1992, against Bosniak villages in the rolling hills on the west side of the Sana river, known as the "Brdo." The Serb forces entered village after village repeating the same pattern — rounding up the villagers in the main square, killing prominent community members such as imams, politicians, academics, or business owners, usually in a spectacle of brutality intended to instill terror in the others, to make them flee never to return. Petty scores from work, school, football fields were settled on the spot, often with a knife.

The scale and brutality of the violence unleashed upon the non-Serbs of Prijedor shocked the international public opinion when a group of British reporters reached the camps in Omarska and Trnopolje in August 1992. In an emergency meeting of the UN Security Council, Lawrence Eagleburger waved the cover of Time Magazine depicting an emaciated inmate of the Trnopolje camp behind barbed wire, reminiscent of Holocaust images, and implored: “Have we forgotten the promise of ‘Never again?’”

This outrage catalyzed the order of the UN Security Council for a commission of experts to be formed to investigate claims of crimes against humanity in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Led by a renowned expert on international humanitarian law M. Cherif Bassiouni, the commission collected evidence that spoke of widespread crimes against humanity, breaches of Geneva Conventions, and, yes, genocide.

The findings led to a historic decision — the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY), the first international war crimes court since the Nuremberg and Tokyo tribunals, was established. The crimes committed in Prijedor formed the basis of the commission’s findings, giving this small Bosnian community an unfortunate reference in the history of international justice.

The first case before the ICTY was that of Duško Tadić, one of the guards in the notorious Omarska camp, and over the years the ICTY indicted 43 persons from Prijedor, making it a municipality with the largest number of war criminals convicted before international courts in the world. After the Dayton Peace Agreement was agreed in November 1995 and officially signed on December 14th in Paris, Bosnian national courts continued this work and indicted another 65 persons, with several trials ongoing, including for crimes in the village of Zecovi.

Despite these numbers, victims’ families in Prijedor still meet the killers of their loved ones who have escaped justice on the street every day. The authorities led by the mayor Marko Pavić work hard to create an atmosphere where perpetrators feel safe and victims are left to themselves to see their loss acknowledged and redressed. In Prijedor, they do. As witnesses coming forward to testify, as activists monitoring the work of investigative and judicial bodies, in whatever form of engagement that is required, they lead the way to see justice done.

Fikret, a social force of one

I first met Fikret Bačić, the father of the murdered Nermin and Nermina, ten years ago while investigating the killings of children in Prijedor for a television program I produced together with a couple of friends. One hundred and two children were killed in Prijedor over several months in 1992, mostly in massacres like the one in Zecovi or in individual raids on Bosniak and Croat homes during the campaign of “ethnic cleansing.”

I was born and grew up in Prijedor. Much of the violence that was inflicted on the non-Serbs of my hometown remains incomprehensible to me, largely because of its terrifying intimacy. Still, on a good day, I can see a way forward, a way to overcome this poisonous legacy through genuine acknowledgement, accountability, education, and strong institutions that can be trusted. However, I struggle to fathom how one finds the strength to make sense of life after such a horrific loss like Fikret’s, how to not give up on people and society.

Fikret has a quiet, measured demeanor and an almost imperceptible dark shadow under his brow; but his eyes leave no trace of doubt about what defines him — relentless pursuit of his goals. And just as when we first met, his goals remain crystal clear, his focus unwavering: truth about the circumstances of his loved ones’ deaths and the location of their bodies, acknowledgement by the authorities, and justice for the perpetrators. And pursue these goals he has, against all odds.

“It was as if I had not only the perpetrators but the entire state apparatus against me all these years,” states Fikret flatly as we sit in the living room of his rebuilt house in Zecovi from which he runs a store frequented by both Muslims and Serbs from the area. Fikret drags calmly on a cigarette as the incredible story unfolds:

“As soon as I returned to Bosnia from Germany in 1998, I approached the police in Sanski Most, where I was living at the time, to report the killing of my family members. I had heard from Zijad, who survived the massacre, what happened and from bits and pieces I collected from him and some other people, I could name four of the men who were in that group of soldiers.”

“The police took my statement and said that the file would be transferred to the cantonal prosecutor in Bihać, since this office had jurisdiction over crimes committed in my village. A year passed, two years passed, nothing. I inquired to check on the progress and found that the statement never left the police archive. I was told that if I wanted to see something done I had to take the file to the prosecutor myself. So I did. The cantonal prosecutor took the file and promised the case would be expedited as a matter of priority. Another year passed.”

“In the meantime I returned to my home in Zecovi, right amid the people who had killed my children, I was seeing them every day. Days pass, we were living in a small village, people talk. Word came to me that a man, the brother of one of the commanders of the group that committed the massacre, was ready to tell me what happened. He was imprisoned for some other crime and wanted to trade information for leniency. I could not bring myself to face him, I didn’t know if he was among my children’s killers, but I passed on the information to an agent of the state investigation agency who went to see him in prison. He told everything, gave everyone up, including his own brother. A crucial witness, his statement was pure gold. As soon as he served out the 2/3 of his sentence they let him out and he returned home. Word spread about him testifying, he was not hiding it at all. A few months later he was gunned down at his doorstep. Somebody drove to his house in the middle of the night, called his name, he came out and they cut him down with a Kalashnikov. Clearly it was someone he knew, otherwise he would not have come out just like that. The local police later said it had to do with drugs. I don’t know, I just know he would have been a key witness in the trial. At least we have his statement though.”

I don’t want to destroy my life over that scum, it would make me just like them. But I can tell you that I felt a great deal of pleasure seeing them in the dock and testifying against them. That is my victory.

“I waited another year, and it became clear that the cantonal prosecutor would do nothing. The one in charge of my file went on maternity leave and her successor told me I should ask for the case to be transferred to a jurisdiction closer to Prijedor, as if it was not a matter of criminal procedure and law but my own whim where the case was to be handled. I refused. I knew that the court in Republika Srpska would never fairly investigate the case. [The Dayton Peace Agreement left Prijedor in the Serb-dominated administrative entity Republika Srpska.] This is the end, I thought, nothing will ever be done. And then the War Crimes Chamber was established in Sarajevo and I went the first chance I got. I spoke to an international prosecutor there, Nick Koumjian, who promised that they would investigate the massacre as a matter of priority. He prosecuted Prijedor cases in The Hague, they left a mark, I guess. This was in 2006. Just as I thought that I would finally see a trial, he left and the case was handed over to another prosecutor. I could tell you stories of the ping-pong that ensued, the countless meetings I had with prosecutors, alone and together with other victims’ families, former camp detainees, anyone who would come with me to try and see something done. The file went from Arnela to Nazif, from Nazif to Bahrudin, from Bahrudin to Nick, from Nick to Džemila, Džemila to Ozrenka, finally from Ozrenka to Izet.”

“Throughout that time I never gave up. I begged Zijad to testify. I found other witnesses. All the time seeing the killers on the street every day. Fifteen years like that, until last November, when these fourteen were arrested. Serbs from Rasavci often come to my store. One of them told me after the arrests: ‘I respect what you are doing. If I knew who the killers of my family were, I would shoot them myself.’ I don’t want to do that, I don’t want to destroy my life over that scum, it would make me just like them. But I can tell you that I felt a great deal of pleasure seeing them in the dock and testifying against them. That is my victory.”

I sit speechless, feeling ridiculous and small in Fikret’s presence. For this is not the only fight he has carried over the years:

“I asked every one of my neighbors to tell me what happened with their bodies, but they don’t want to say. I tried everything, begging, threatening to sue them, nothing. I had a man, a Muslim, come to me and demand 1,000 Marks [approx. $600] per body, 33,000 in total, to tell me where they are buried. I chased him away, a vulture.”

“There are all kinds of stories. An old woman in a nearby village saw a truck carrying bodies of women and children disappear in a forest next to her house. A Serb man confirmed this and was supposedly ready to take me to the spot where they were buried, but he died days before we were supposed to meet. I went there, to as far as the road goes, you can still see the tracks left by the truck, but I could not find the spot. Another man claimed they were buried in Tomašica mass grave, but they haven’t been found there so far. I wait for some piece of news, some lead, something. Every day I expect to find them.”

“I know the Serb policemen who were in charge of escorting such trucks, but they refuse to talk. Many are pensioners now, I see them strolling through Prijedor as respected citizens, without a shred of conscience, no remorse, no empathy for the families who are still searching for their kin. And the authorities encourage this silence.”

Indeed, sometimes it seems that victims’ families speak with more anger and desperation about the leaden silence from their Serb neighbors about what happened in 1992 than the crimes themselves. This hurtful silence, the denial of their suffering, comes as the final betrayal of everything that was shared in the past, of who we believed we were. This denial is not organic, somehow inherent to Bosnians, Serbs, or Prijedor folk, but carefully and relentlessly constructed as the backbone of wartime strategy of separation of formerly closely knit, ethnically mixed communities by those with the most power: Prijedor’s political and religious establishment. In Prijedor, now completely Serb-dominated as a result of a carefully executed policy of extermination, it is the municipal authorities led by Mayor Marko Pavić, a former intelligence officer active in Prijedor during the conflict, that are primary perpetrators of denial. In the most recent and most blatant of examples, Pavić and his administration became the main obstacle to an initiative to build a memorial in the city’s center to the 102 Prijedor children killed in 1992. The reason: their ethnic identity and the fact they were killed by Serb forces who are celebrated as heroes and defenders of their people. The initiative to build the memorial is driven by the parents of the killed children and has attracted the support of activists from Prijedor, but also the rest of Bosnia and internationally. At the helm of it, again, is Fikret:

“We have been demanding this for years. There are countless monuments to Serb soldiers in the city, and we don't mind. They even put the names of convicted and accused war criminals in the soldiers' memorial in the city center. This doesn't bother them, but the mayor says that a memorial for the killed children would be “politically sensitive.' I met him several times and it’s always the same story. He appears on television talking about Prijedor being a multicultural city, a multiethnic community, how he is building a city for all its citizens . . . All lies. Here is a chance for it to become such a city.”

“What can you possibly have against a memorial to killed children? Pavić says how he is not against it as a humanist, but as a politician he asks why isn't there a similar thing for the Serbs in Bosniak-majority areas, why does Prijedor have to be first? Again a lie, as there are such monuments that honor Serb children in places like Konjic, for example. [Konjic is a city in southern Bosnia and Herzegovina now dominated by Bosniaks.] But we are not asking for a monument exclusively for Bosniak children, but all children of Prijedor. There are Croat children who were killed and one Serb child, we want them all included. But the response is always a “no,” that it is not [the mayor] who can make that decision, that it is the municipal assembly, the usual deflection and manipulation tactics.”

“So we decided to take the legal route. The municipal statute provides that the assembly has to hear an initiative backed by at least 1,000 voters from Prijedor. We gathered 1,275 in a matter of weeks. I personally delivered the signatures, all stamped, all according to protocol. The president of the municipal assembly has avoided me ever since. We had some of the most renowned experts and activists from around the world demand that the memorial be allowed. Still they refuse.”

“They don't even realize what a historic opportunity they have to do the right thing for themselves, for the city, and its future generations.”

On that note we finish the coffee and the conversation, Fikret apologizes for cutting the meeting short: the municipal assembly is meeting today and he will be there, to remind them — again — of the legal obligation to discuss the memorial.

Siege of the fortress of silence

In November 2013, investigators of the Bosnian Institute for Missing Persons uncovered the largest mass grave in the country. Hidden in the desolation of an abandoned iron-ore mine in Tomašica, some 12.5 miles outside Prijedor, the pit contained the remains of more than 800 people killed in the camps or at their homes in raids by Bosnian Serb forces. It took more than 20 years for the families to locate the bodies of their loved ones, after a tip off by an unnamed Serb man who showed the investigators where to dig. With the bones of the men, women, and children buried in Tomašica, a disheartening truth emerged about the effects of the policy of “separation of peoples” implemented by the Bosnian Serb leadership, through dehumanization, violence, and the politics of denial.

“The man who led us to the grave told us how the local Serb villagers all these years ago complained secretly to the municipal authorities, asking for the mass grave to be relocated because of the stench and the fear that it was polluting the ground waters. But they never said anything publicly. Some of the people in this pit were their neighbors, but they kept silent and probably would never come forward to tell the families,” said one of the investigators.

What conditioned these villagers from houses along the road used by trucks and heavy machinery carrying dead bodies to keep silent all these years, while passing the family members of the victims on a daily basis? Have we always been this heartless, this hostile to one another? Was our shared past one big lie? These thoughts occupy me as I sit in a garden of a local bar that looks on “Kej,” a lush green park in Old Town where generations of Prijedor teenagers, me included, spent many a summer night gathered around a guitar, professing first declarations of love, reciting pathetic poetry, or some such silliness. The huge chestnut trees still tower over the park, bearing witness to some new teenage poets who hog the park benches below their thick canopies. Everything seems just as it was all those years ago. But nothing is.

“There is still this political and ethnic separation, which is not so visible in everyday life. But if you veer off mundane topics and want to talk about what happened during the war, you can see how real the separation and conflict still are,” says Goran Zorić, an activist of the Youth Center Kvart, in Prijedor, as he takes a long drag from a hand-rolled cigarette.

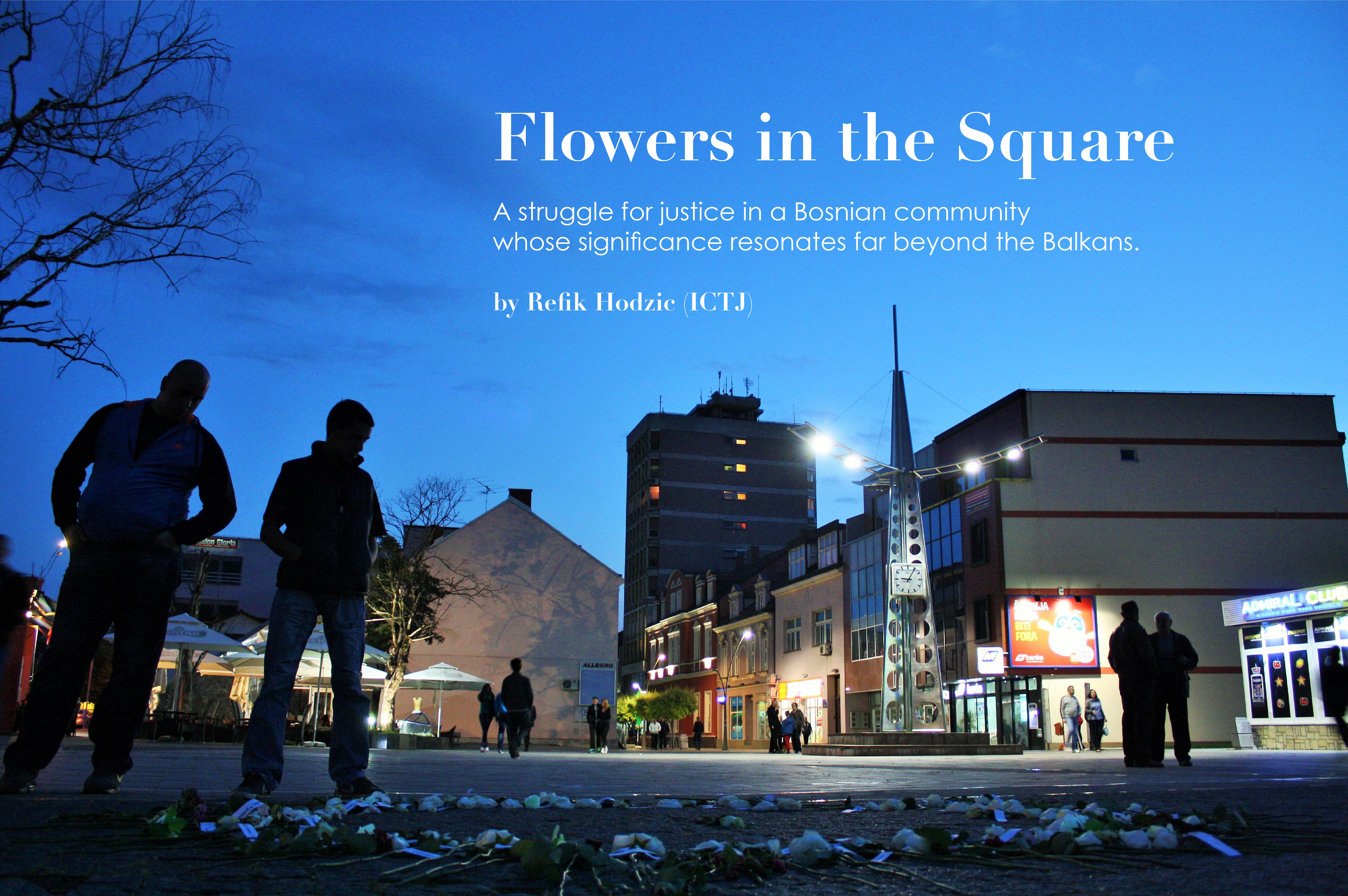

Goran and his group shot to the center of public attention in Bosnia in 2013 when they joined the families of Prijedor victims in a protest against the denial and ban on public commemoration of crimes committed against non-Serbs in the city by Mayor Pavić. A year earlier, associations of victims’ families and camp survivors launched a series of protests, culminating in the “White Armband Day” campaign. “White Armband Day” is marked every May 30, when victims’ families and activists gather in Prijedor’s main square to demand that local authorities acknowledge crimes committed in 1992 and allow a memorial to the 102 murdered children. They wear white armbands as a reminder of the order by Serb authorities issued on May 30, 1992, for all non-Serbs to wear white armbands when they leave their homes to show loyalty to the “Serb Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina.” They also lay 102 roses bearing the names of the killed children in the main square, in place of a permanent memorial. Roses are left on the square long after the protesters are gone and the interaction of passers-by with this symbolic form of protest represents one of the most powerful catalysts of dialogue about the past in Bosnia and Herzegovina. When the Kvart youth activists joined the protest, and when Goran, wearing a white armband, addressed the mayor demanding he lift the ban and allow memorials to non-Serbs in Prijedor, a huge barrier was smashed. For Goran and his friends are Serbs.

“The narrative constructed by Serb politicians is that the stories of Muslims suffering during the war are blown out of proportion and that they are used as political tools to destroy Republika Srpska, to vilify the Serbs. So many ordinary people gladly go along with this, or simply try to avoid talking about it. Such an attitude is the foundation of this poisonous situation we live in today, what we struggle against.”

And struggle they do, despite the public attacks by Mayor Pavić, and not so public but dangerous threats from local neo-Nazi and Serb extremist groups. In what they are doing, Kvart are part of what is possibly the most authentic grassroots activism seeking acknowledgement and accountability in Bosnia and Herzegovina, making Prijedor a unique local environment. One side of the picture is painted by the scale of the crimes, the denial, and continuous and systematic suppression of victims’ rights by municipal authorities, while the other features an unwavering fight of victims’ families, survivors, and activists of all ethnicities to see perpetrators taken off the streets, to document the crimes, to do justice to the memory of the victims. If I was asked to name someone who personifies this activism, it would have to be Edin Ramulić.

I met Edin in January 1996, less than a month after the war officially ended, in Paris. He was fresh out of the Bosnian Army, a decorated officer, who rose through the ranks on the account of his bravery in battle. Although it would be months before he swapped military fatigues for civilian clothes, it was clear he was a journalist at heart. We would later form a radio station and a magazine, whose main editorial policies were connected to the right of refugees to return and to the investigation of crimes committed in 1992.

It was not hard for me to understand his drive to investigate and document war crimes. He was searching for a very personal truth. Edin’s father and brother were taken to one of the most notorious camps — “Keraterm” — and never seen alive again. Edin himself ended up in a different camp, before he was deported to central Bosnia together with thousands of other non-Serbs. Years later, we would part, I would join the war crimes tribunal in The Hague and he started working with a women’s group, Izvor, whose main mission was the search for the missing. The work this organization has done over the years is of enormous historical significance:

“What is different here as compared to the rest of the country has to do with the group of people who worked in an organized, systematic way ever since 1997, 98, after the war stopped. We did concrete things that have not happened elsewhere: Bosnia still doesn’t have an official register of victims, but we created a database of victims for Prijedor as early as 1998 and published our Book of the Dead and Missing. There is no public memorial for non-Serb victims anywhere in Republika Srpska, but here — we placed one in a “guerrilla action” in front of the “Keraterm” camp in 2003. Nowhere in Republika Srpska did non-Serb victims protest publicly, in the main street, we were the first to break that barrier. We launched campaigns like “Stop Genocide Denial” and “White Armband Day” that drew in tens of thousands of people. We supported countless witnesses to come forward and testify in war crimes cases before different courts. All this has resonated and created a front in Prijedor where denial and silence about the past are the enemies. But, so much more needs to be done, so much more. And the problem is not only in the actions of the mayor and his ilk, it is also us,” Edin sighs and his mood darkens.

“People have been reduced to members of a collective, on all sides. In the construction of ethnic victimhood narratives we reduced all these victims to their deaths. We don’t talk about them as individuals, that they were doctors or had a career in sports, in science, built something, owned something. That has become meaningless. Only the number is important, the bigger the number the bigger “our” pain and “their” responsibility, which is the backbone of ethnic politics here. In a way, we kill these people again by reducing them to their collective identity, which we don’t even know they would choose if they were alive.”

The firm segregation of victims along ethnic lines that Edin speaks about serves one specific purpose: preventing the possibility of empathy for those who are not on “your side,” even if they are former neighbors, children, the purest of innocents. This prevention of empathy is a crucial tactic in the ongoing pursuit of wartime political goals and the fight for the truth about the war fought out in the political arenas, in textbooks, in churches and mosques, in the media. It is what allows for denial to flourish despite the overwhelming body of evidence about what happened, countless court decisions, truth-telling exercises, databases, and documents. It is what severely limited the societal impact of various transitional justice initiatives.

The intimacy of violence has left deep scars in Prijedor. Seemingly overnight, neighbors turned into perpetrators of incomprehensible violence. Today, twenty years since the end of the war, mothers of the disappeared often live next to those who disappeared their children. Silence and denial about the past continues to be imposed on both, with little space for an honest reckoning. Mina Delkic refuses to live in such silence. Click here for a photo essay of her story.

Although the activism around the initiative to build a memorial to the 102 children murdered in 1992 has exposed this absence of empathy in Prijedor more than in other places in Bosnia where the silence is not even challenged, this inhumane phenomenon is by no means limited to this community. It is widespread and its primary targets are the young.

“It is sad that after twenty years, after so much money was invested, so many strategies, so many ideas, so many lies, so many truths, that we are at the point where we can say that the only thing that the Dayton Peace Agreement achieved is that nobody is shooting at you, but we are still divided. Every year I teach kids at the Human Rights Initiative Summer School who were born during or after the war and two years ago when I asked them whether they felt they lived in peace and if they felt the war was over, all of them told me in one voice, “No, the war is not over,” explains Nidžara Ahmetašević, a journalist and a leading scholar on the role of media in the Balkan conflict and the subsequent transitional justice process.”

Goran Šimić, a professor at the International University of Sarajevo and the author of one of the most serious analyses of the transitional justice process in Bosnia, agrees: “Crimes we have committed against each other are not recognized here if the victims are not of your ethnicity. We don’t recognize other people as human beings who have the potential to suffer just like us. At the same time, we are teaching our children to be smarter than we were, to join the right political party, to be much cleverer than us to achieve some small goals. But we are failing to invest in a narrative that will show them that those who do not learn from the past are doomed to repeat it.”

Listening to these expert voices, the huge significance of what people like Edin, Goran and fellow activists are doing in Prijedor grows clearer in my mind. The story told by their performance commemorating 266 murdered women and girls in Prijedor’s main square is like a serum against the poison of denial. Each name on each of the 102 roses for the murdered children left every May 30th in the city’s main square to symbolize the absence of a memorial, each of the 102 empty school bags they paraded through the main street told the story that will stick with any citizen of Prijedor who caught a glimpse of them, no matter how hard they try to suppress empathy. There is nothing more powerful than a story to break down the walls of denial. And in Prijedor, nobody can tell a story like Darko Cvijetić.

Darko is an actor, a theater director, an essayist, and a poet. He is a quiet, calming presence, his beard streaked with white strands, his glasses not entirely concealing the sediment of the last two decades of living in Prijedor accumulated beneath his curious gaze. He was here during the war, he has seen it all, from the war on the Serbian side to the persecution of his non-Serb neighbors. His eyes show it. We drink coffee after coffee in the former “Officer’s Club” at the bottom of Prijedor’s main street, where I played my first game of pool as a teenager mesmerized by Paul Newman’s “Hustler.” It has been a long time since we saw each other, we talk about everything at once, gushing, about Huddersfield, his new play, my plans for a documentary, his daughter, my children, Prijedor’s nightlife that is a mystery to both of us, before I regain my focus and we begin discussing the work he has done to shatter the silence on Prijedor’s dark past. Darko has authored some of the most powerful poems I have ever read, recently compiled in a book titled Mass Postcards from Bosnia. I ask him about the silence in Prijedor, the absence of empathy, what drives him to write the way he does.

“I am trying to capture it in a poem, this coexistence of the killer and the victim, this relationship, this situation which is now escaping rational analysis. I have seen things, where people as harmless as bunnies become military commanders, and who after they stop being commanders go back to “normal,” to being bunnies again. After killing they go back to working in a warehouse, to waiting for their pension, waiting for the life to expire in a stupor. There are very few aware people here, the majority are so easy to manipulate. This context was created where if leaders told them to wear horns the vast majority would wear horns. It is insane, but that is how it is. That is where I look for reasons for such acts, like not allowing a memorial for the killed children. I keep telling the [Serb] people here that this is just a handful of people, our fellow Prijedor people, who are seeking acknowledgement. To close that door, to be allowed to mourn, to be allowed to cry, nothing more. Let me chose when I want to come and cry for my child. That is a minimum of humanity we must allow for. And it will happen, mark my words, perhaps even the most radical of [Serb] nationalists will in the end build that memorial. That has to happen, not because of you or me, but because of the cosmic justice. These children must not be left unmourned.”

I walk home in a daze after talking to Darko for hours. As I pass through the main street of my hometown without recognizing anyone or being recognized, a thought, a comforting realization forms and settles somewhere deep within. No fortress of silence built around Tomašica can withstand the might of these words from Darko:

EXHUMER’S POEM*

Once we found

A transplanted heart

In a skeleton,

Not rotting

Should’ve seen it:

Still beating and thudding

And as there was no blood

It had nothing to pump

Aortas wheezing

Chambers rattling

Love’s arrow (the one from the fairy tale)

Greasy

Quivered

In a skein of veins

So we took it

What else can you do

Perhaps a mother

Knows

Whose is the rib cage

The secondary heartgrave

*Translated by Mirza Purić

Epilogue

The systematic crimes targeting non-Serbs in Prijedor, in which 3,173 people were killed, their deaths — or rather the manner in which they died — marked the moment after which the community that inhabits this green valley was changed forever. It has deeply and painfully poisoned the survivors with hate, fear, and guilt. The subsequent denial by today’s residents of Prijedor of what happened, and their refusal to face the truth, have made the effects of that poison long lasting and endlessly difficult to cure.

The consequences of the extermination campaign targeting non-Serb citizens of Prijedor are permanent. Today, only the malicious, blind, and irresponsible can doubt this reality.

The planned removal of Bosnian Muslims and Bosnian Croats from this area was executed systematically and brutally. And successfully. The facts about the inception and implementation of this criminal enterprise by the Serb authorities have been established beyond any reasonable doubt before the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia in The Hague and numerous independent researchers.

The return of a certain number of those expelled has somewhat affected the outcome of the extermination campaign, but the full extent of it will be apparent in the coming years. In ten years, as we count the few remaining non-Serbs in Prijedor, the picture of the dimension and long-term nature of the crimes will be crystal clear.

This does not mean that Prijedor has forever lost every trace of the existence of non-Serbs.

Similar turning points occurred here in the past — World War II, with the slaughters and the persecution of Serbs from the Prijedor region by Ustashas is only one of them. People continued to live and the community slowly healed, albeit wounded and changed. This process is taking place as we speak, despite the best efforts of some to achieve the opposite.

Still, the fact remains that mass murders in Prijedor, Kozarac, Brdo, Ljubija, and Brisevo, executions and torture in Omarska, Keraterm and Trnopolje, rapes and deportation, humiliation, and plunder committed against non-Serbs two decades ago have shaped our present and our future.

And what now? Are Prijedor’s people doomed to live their lives infected by hatred, fear, guilt and deep mistrust of the other? Will atrocities in which children were burned alive with their mothers be eternally celebrated as victories over “them”? Is forgetting the only hope? Will the opposing narratives of the bloody nineties serve as the fuel for some future slaughter? Do we have the strength to achieve reckoning with the period in which we lost “our Prijedor” forever? Do we have the courage to realize that we today live in something we could make “our Prijedor” again, if we muster the strength to repent and forgive?

I don’t know. The answers to these questions lie beneath the veil of time and our willingness to take on the enormously difficult and excruciating task of dealing with our recent grisly past. Who knows whether any of us who nostalgically remember Prijedor, whose flowery courtyards hid the play of 102 children from the ring of flowers, will live long enough to find out? As soul-destroying as it may be, we must be ready to accept that we will not.

Our Prijedor is gone, never to return. Its soul has been sacrificed for the “strategic goals of national interest” and the creation of a state in which one group will prosper at the expense of the others; for the creation of entities where yesterday’s friends and neighbors, workmates, and pals from the school football team were reduced to sinister enemies that need to be eradicated, even if it meant sliding into self-imposed isolation. Our Prijedor was buried with the innocents whose names echo on the pages of our Book of Dead and Missing just as they echoed in the bloodcurdling darkness of Omarska and Keraterm hangars.

Our Prijedor will live in our stories about fairytale childhoods from Kozarac, the golden sunsets of “Kej,” and shy first advances at Ramo’s Café — stories we will continue to tell, consumed and melancholic, to our disinterested children whose lives will be rooted elsewhere — in Chicago, Ljubljana, Melbourne, Sanski Most. That Prijedor will live as long as our memories live and the trace of them we leave behind.

The 3,173 faces in the Book of Dead and Missing are windows into entire worlds that the Prijedor of the past was composed of. They are the guardians of the truth about a city executed together with its citizens. The stories about them, who they were and who they could have become, will be told as long as this invaluable document lasts and as long as there are people like Darko Cvijetić to tell them.

Prijedor has a chance to be a community where humanity will be a value above the myths about ethnic superiority, inferiority of “others,” celebration of crimes and discrimination, only if it faces the truth about the crimes that changed it so.

Yet, I would dare say that the greatest significance of this struggle lies not only in providing some comfort to their families. I am convinced that the results of the efforts described in this text will be far more valuable to the present and future citizens of Prijedor as they will ultimately become integral to a history textbook about the city in which they live.

For Prijedor has a chance to be a community where humanity will be a value above the myths about ethnic superiority, inferiority of “others,” celebration of crimes and discrimination, only if it faces the truth about the crimes that changed it so. It is less important to this process what percentage of Serbs, Bosniaks, Croats, Jews, Romas, Ukrainians, or others will live in that community. But it is important that the reckoning with the past is honest and thorough, and that the outcomes of this reckoning are built into the history of Prijedor in a manner accessible to its present and future inhabitants.

At the end of that painful, but decisively important process awaits the day in which the story of the life and death of little Nermin and Nermina Bačić will be told as homework by some Ana or Petar, pupils of Prijedor’s school, after their visit to a memorial with names on a ring of flowers. A memorial whose natural place is in Prijedor’s main park.

***

After a year of delays and broken promises, on December 8, 2015, the Prijedor municipal assembly overwhelmingly voted against discussing the permit for a memorial to the 102 children murdered in 1992 to be built. On December 10, Fikret Bačić stood in Prijedor’s main square, before a small crowd of people huddled under umbrellas in the cold rain and declared:

“My name is Fikret Bačić and I speak to you on behalf of parents of 102 children murdered or disappeared in Prijedor from 1992 to 1995. I speak to you on behalf of my daughter Nermina and my son Nermin, who were six and thirteen when they were killed.”

“More than anything, I speak to you as a citizen of Prijedor who has always regarded this city as my hometown. My hometown in which I planned to grow old, and watch my children grow up and love this city as much as I did. Tragically, I am speaking to you today as a parent of murdered children, as their father, and one of the people who launched the initiative to build a memorial for them.”

“Over the past year, we received countless promises from the president of the assembly and the mayor that our petition would be discussed and memorial allowed. All these promises were broken. This clearly speaks about the continued discrimination against non-Serb citizens of Prijedor and the inhumane attitude of the people who are supposed to represent all citizens of this city. Their heartlessness has reached the depths where they refuse to allow a memorial for our dead children to be built. Above all, by refusing to discuss the petition they are breaking the statute of the city and the law prohibiting all forms of discrimination in this country.”

“On that basis, we intend to file criminal charges against the president of the assembly, the mayor and all those with legal obligations in this case and continue our struggle for acknowledgement through legal means. We will not give up until the memorial is built.”

“Our children will be remembered and mourned.”